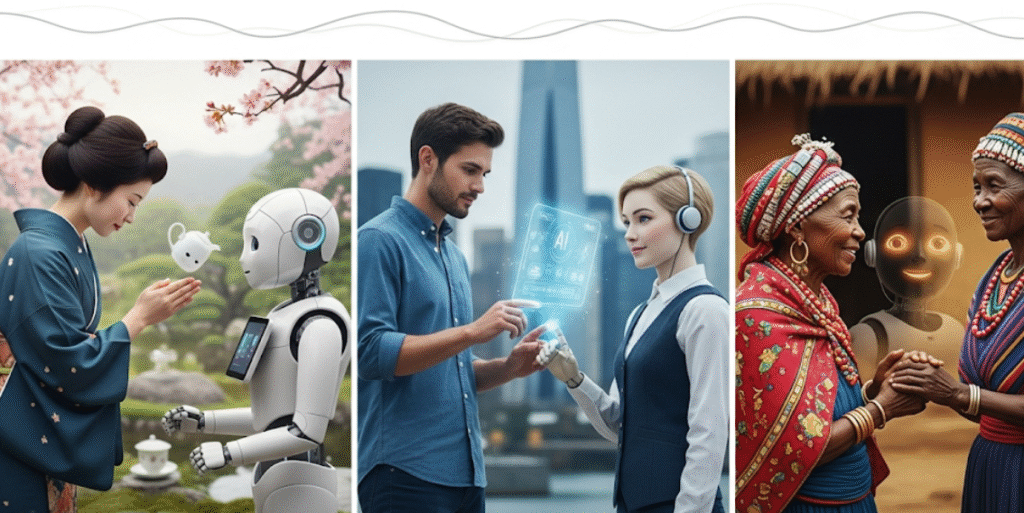

As we navigate the digital age, AI is transforming how we connect, not just with tools but with entities designed to feel like friends, confidants, or even romantic partners. AI companionship—where chatbots, virtual assistants, or robots provide emotional support or social interaction—is gaining traction worldwide. However, the way people embrace these technologies varies significantly across cultures. Research suggests that cultural backgrounds shape attitudes toward AI companionship, influencing everything from user acceptance to ethical considerations. This article explores these differences, drawing on studies and real-world examples to understand how culture molds our relationship with AI companions.

Cultural Perspectives on AI Companionship

Attitudes toward AI companionship differ markedly across regions, with East Asian cultures often showing greater openness compared to Western ones. A 2025 study in the Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology found that East Asians, particularly those from China and Japan, are more likely to enjoy and approve of social interactions with AI chatbots than their Western counterparts. For example, East Asian students in Canada expected to enjoy chatbot conversations more than students of European descent, and Chinese and Japanese adults showed more positive attitudes toward human-chatbot interactions than Americans.

In East Asia, AI companions like XiaoIce, with over 660 million registered users in China, are treated as friends or confidants, reflecting a cultural comfort with technology in social roles. Similarly, Japan’s use of humanoid robots like Pepper for elderly care highlights a societal acceptance of AI as companions. In contrast, Western cultures, such as those in the United States and Europe, often approach AI companionship with skepticism. While platforms like Replika have millions of users, concerns about privacy, authenticity, and over-reliance on technology are more pronounced. These differences stem from a complex interplay of cultural factors.

Factors Shaping Cultural Attitudes

Several key factors explain why attitudes toward AI companionship vary across cultures:

- Anthropomorphism: East Asians are more likely to attribute human-like qualities to AI, viewing them as having some degree of consciousness or emotion. This tendency, known as anthropomorphism, makes it easier to form emotional bonds with AI companions. Research shows that Chinese participants score higher on anthropomorphism than Americans, with Japanese falling in between.

- Religious and Philosophical Beliefs: Eastern religions like Shintoism and Buddhism, with their animistic roots, blur the line between humans and non-human entities. In Shintoism, spirits inhabit all things, while Buddhism suggests that anything can achieve enlightenment. This worldview makes AI companionship more acceptable in East Asia. In contrast, Western religions like Christianity often emphasize a clear distinction between humans and machines, fostering caution toward AI in intimate roles.

- Historical Context and Technological Exposure: East Asian countries have a longer history of integrating robots into daily life. Japan, for instance, has pioneered social robots like Pepper, used in retail, education, and healthcare. This exposure normalizes AI in social contexts. Western societies, however, have traditionally viewed technology as tools, not companions, which may explain their reserved attitudes.

- Societal Norms and Values: Collectivist cultures in East Asia prioritize social harmony and connections, viewing AI companions as part of the social fabric, especially in addressing loneliness. Individualistic Western cultures often prioritize human-to-human bonds, seeing AI companionship as a potential substitute rather than a complement.

These factors create a cultural lens through which AI companionship is perceived, influencing its acceptance and use.

Real-World Examples of AI Companionship

To illustrate these cultural differences, consider the following examples:

- XiaoIce in China: Launched by Microsoft in 2014, XiaoIce is a social chatbot with over 660 million users. It engages in conversations, offers emotional support, and participates in group chats, often treated as a close friend. Its success reflects China’s cultural openness to AI as a companion, driven by anthropomorphism and societal acceptance of technology in social roles.

- Pepper in Japan: Pepper, a humanoid robot, is widely used in Japan for tasks like customer service and elderly care. In a society grappling with an aging population and increasing loneliness, Pepper provides companionship, demonstrating Japan’s comfort with robots in intimate roles. This acceptance is rooted in cultural factors like animism and long-term exposure to robotics.

- Replika in the West: Replika, an AI chatbot designed for emotional support, has an estimated 25 million users globally. While popular, it faces scrutiny in Western countries over privacy concerns and the authenticity of AI relationships. Some users value its ability to simulate deep conversations, while others worry about over-reliance, reflecting a cultural preference for human connections. In addition, services such as 18+ AI chat have emerged, catering to users seeking more mature or intimate interactions with AI companions. Their reception also varies culturally, with East Asian contexts tending to normalize AI intimacy more than Western ones.

These examples highlight how cultural contexts shape the adoption and perception of AI companions. In Japan, for instance, societal changes like increasing solitary lifestyles have boosted the appeal of AI companions, with some even forming romantic bonds through virtual weddings with AI characters.

Implications for AI Development and Adoption

The cultural differences in attitudes toward AI companionship have significant implications for developers, marketers, and policymakers:

- Culturally Sensitive Design: AI companions must be tailored to cultural preferences. In East Asia, emphasizing human-like qualities may enhance appeal, while in the West, transparency about AI’s limitations could build trust.

- Targeted Marketing: Marketing strategies should reflect cultural values. In East Asia, highlighting emotional and social benefits may resonate, whereas in the West, focusing on practical applications and privacy assurances might be more effective.

- Ethical Considerations: Ethical frameworks must address cultural concerns. In individualistic cultures, there’s greater worry about AI replacing human relationships, necessitating guidelines to position AI as a supplement, not a substitute.

- Global Strategies: Companies expanding globally must adapt to local attitudes. A successful product in Japan may need significant changes to gain traction in Europe or the United States.

- Future Research: More studies are needed to explore how cultural attitudes evolve with increased AI exposure and to assess long-term impacts on mental health and social cohesion.

| Cultural Factor | East Asian Perspective | Western Perspective |

| Anthropomorphism | High; AI seen as human-like | Lower; AI viewed as tools |

| Religious Beliefs | Animistic roots (e.g., Shintoism) support AI acceptance | Clear human-machine distinction fosters skepticism |

| Tech Exposure | Long history of social robots normalizes AI companionship | Limited exposure leads to caution |

| Societal Norms | Collectivism sees AI as part of social fabric | Individualism prioritizes human bonds |

Conclusion

Cultural differences profoundly shape attitudes toward AI companionship. East Asians, influenced by anthropomorphism, animistic traditions, and extensive exposure to social robots, are generally more open to AI companions. Westerners, with their emphasis on human-to-human connections and concerns about authenticity, approach these technologies with caution. As AI companionship grows, developers must consider these cultural nuances to create technologies that resonate globally while addressing ethical concerns. By recognizing and respecting these differences, we can ensure AI companions enhance human well-being across diverse cultural landscapes.